Electrical energy: volts, amperes, watts, joules - and play-doh

Visualizing the invisible with a child’s toy.

The Electrical Engineering Stack Exchange often gets questions from beginners that basically amount to confusion about just what electrical energy is.

The usual form this takes is someone who has discovered a way to get a higher voltage out of a circuit than the circuit was supplied with. Say, getting 2.2V out of a 1.5V battery. The naive beginner assumes that the circuit is somehow an exception to the law of convervation of energy or the three laws of thermodynamics. Clever folks realize that there’s something wrong and ask what they are missing because they doubt that those laws would be as easy to break as their simple, obvious circuit suggests.

The thing about electrical energy is that you don’t have anything tangible to equate to work or energy as in the classical mechanical physics experiments.

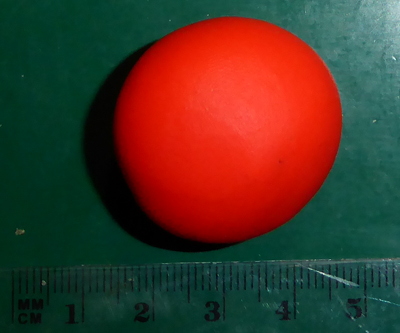

I’ve remarked before that I find it easier to understand abstract things if I can somehow make them more concrete. I’m going to use play-doh to make a tangible model of electrical energy.

To start with, I’m going to give a definition of electrical energy. After that I’m going to break it apart and use tangible things to explain the pieces so that the abtract “energy” has a visible referent. Maybe that will help someone else comprehend electrical energy - hopefully without adding extra confusion.

Electrical energy is measured in joules. Wikipedia has a lot of variations in the definition. All are equivalent, but some are more useful than others.

The definition I am going to use is the following:

\[Energy = volts \times amperes \times time\]Where energy is measured in joules and time is measured in seconds.

1 volt applied to a circuit at 1 ampere for 1 second gives 1 joule.

This is a useful definition for electronics. You can readily measure voltage and current in a circuit using a multimeter or an oscilloscope. Oscilloscopes can also measure time.

Since energy is given by the product of three quantities, I find it useful to think of it as a box or blob.

Like this:

| Blob of energy |

|---|

|

Let’s have a look at voltage, current, power, and energy.

Voltage is the pressure that makes current flow. It is typically measured with a voltmeter or presumed known because you are working with a power supply or a battery. Most folks seem to grasp voltage fairly well, except for those who directly equate voltage and energy and start hollering “over unity” when their voltage boost converter puts out more voltage than they put in.

I’m going to represent 1 volt as a line 1 centimeter tall:

| 1 volt |

|---|

|

Current is the flow of electrical charge. It is typically measured with an ammeter. You really must measure current. Most devices operate on a fixed voltage and draw current as needed from the supply. This is usually the first place where people get confused. They’ll have a 5 volt, 1 ampere power supply and assume that any device connected to it will have to consume that 1 ampere. That’s wrong, but it’s a common misunderstanding. That power supply has an output fixed at 5 volts, but it will deliver up to 1 ampere - nothing forces the consuming device to draw all of the available 1 ampere.

I’m going to represent 1 ampere as a line 1 centimeter long:

| 1 ampere |

|---|

|

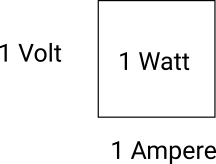

Power is the product of current and voltage. If you apply 1 volt to a 1 ohm resistor, 1 ampere of current will flow and the resistor will consume 1 watt of power.

So what does 1 watt look like? A rectangle, with one dimension measured in volts and the other measured in amperes:

| 1 watt |

|---|

|

Energy is the product of power and time. If you apply 1 volt to a 1 ohm resistor, 1 ampere of current will flow and the resistor will consume 1 watt of power. If you leave that circuit in operation for 1 second, then it will consume one joule of energy.

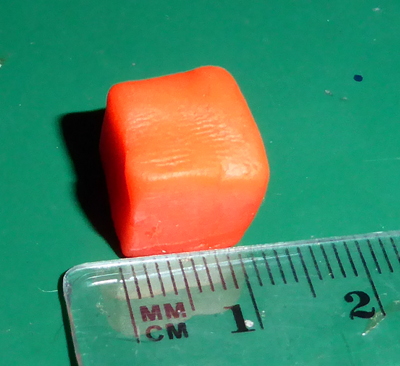

Finally, we get back to the play-doh. 1 joule of energy is a box 1 volt high, 1 ampere wide, and 1 second long:

| 1 joule |

|---|

|

There you have it. My mental model for grasping electrical energy - just a blob of play-doh.

When you go to considering conservation of electrical energy, you have to keep your eye on the volume of that blob. All else is subject to change, but the volume of the blob of energy that goes into your circuit will have the same volume as the blob of energy that comes out of your circuit.

Calculating the volume of a box is simple. $ length \times width \times height$ and “Bob’s your uncle.” Calculating the total energy consumed by a circuit is… never that easy.

It is a rare circuit where you have something as simple as “1 volt applied to a circuit at 1 ampere for 1 second.”

Voltage varies. Batteries have a “nominal voltage,” but that’s not a fixed value in real life. The moment you start drawing current from a battery, the voltage changes. It is higher when the battery is fully charged (or new,) but lower when it is running out.

Current varies. If the voltage from your battery goes down but the load stays the same then the current will go down as well.

Since current and voltage vary, the power varies as well. Even when using a power supply, the voltage varies slightly - and current can vary drastically depending on what your circuit does.

Time is a whole other can of worms. Many components can store energy and release it later. Capacitors and inductors do so, and many devices have built in (rechargeable) batteries. Given that ability to store energy, any measurement of consumed energy also has to account for things that happen after the external power source has been disconnected.

The energy consumed by a simple light bulb and battery circuit might look like this:

| Energy consumed by a battery powered lamp |

|---|

|

The volume of that thing is not so easy to calculate. Since it’s a blob of play-doh that won’t dissolve (too quickly) in water, I could just go all out Archimedes on it and dunk it in a glass of water to find the volume. That works fine for the model. Unfortunately, electricity doesn’t work that way.

To find the “volume” of energy a circuit uses, you typically measure the current and voltage many times per second. From the collected numbers, you can compute the power for each measurement - effectively, you “slice” the volume into thin slabs and calculate the area. The “thickness” of the slabs is given by the amount of time between measurements.

Like this:

| Energy slices |

|---|

|

| Ideally, the slices end up as rectangles - my play-doh model was kind of lumpy since I made it by hand. |

With nice, rectangular slices, the area is easy to calculate. You know the “thickness” in time because you know how often you made your measurements. Voltage of each slab * current of each slab * time between measurements = energy of each slab. Add them all up, and you have your (volume) of energy.

There are limits to how well that works, but it is the basis of pretty much any modern measuring device that computes energy. The faster you measure, the thinner the slabs and the more accurate the final total.

There you have it. The basis of my understanding of electrical energy and measurement in one nearly indigestible blob.