Photographing the invisible - the interesting hardware

Not the hardware store stuff, but the electronics.

RF camera and radio telescope - Table of Contents

Last time around, I went into some of the details of the mechanical parts of the microwave camera.

This time, I’m going to explain the electronics.

I’ll start with a schematic, then explain it by sections.

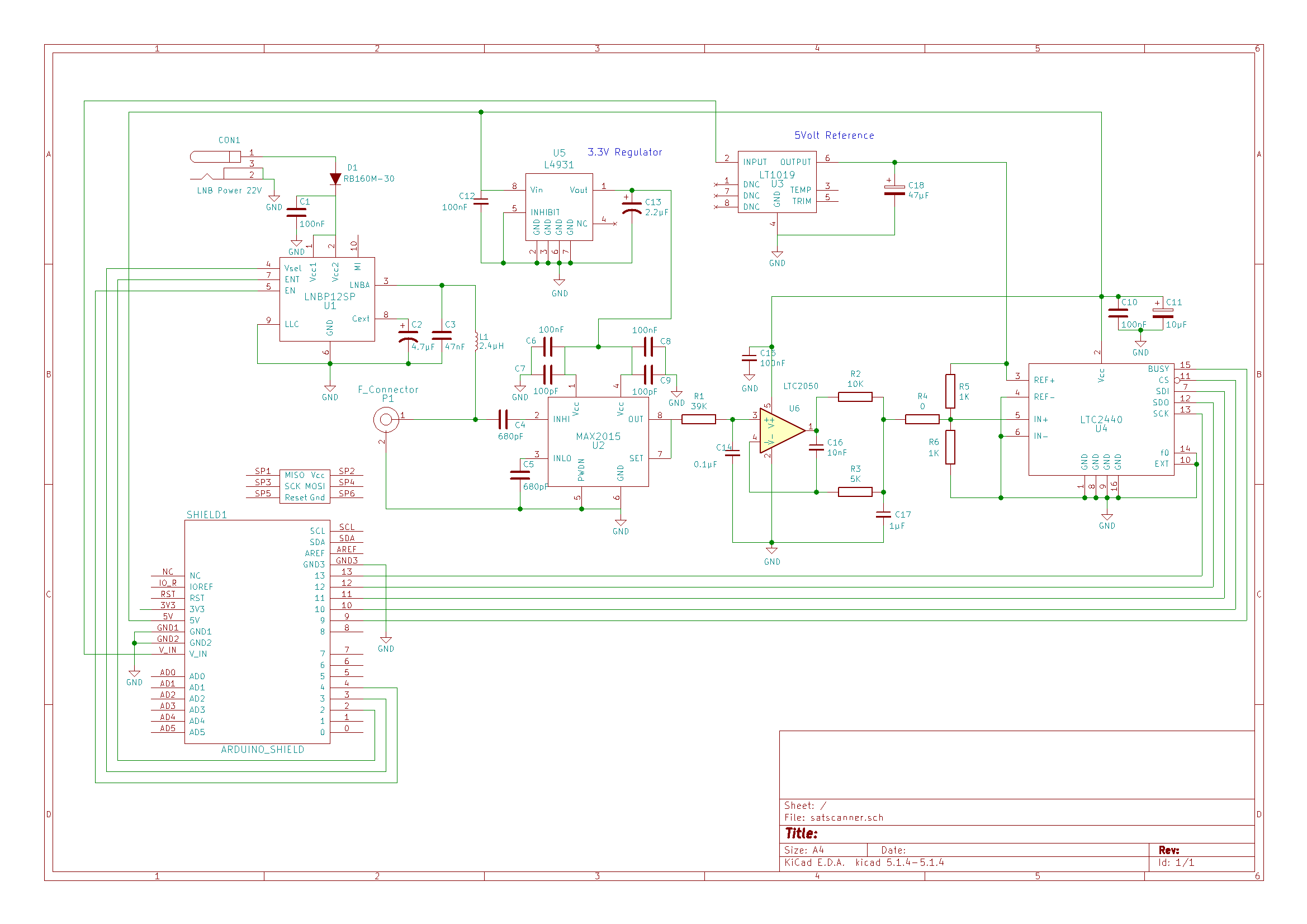

| Karl Arduino shield schematic |

|---|

|

| (Open the picture in a separate window and zoom in to see the details.) |

First, a few notes:

- All polarized capacitors are tantalum electrolytics. Some of the parts require them to be stable. Some people avoid tantalum capacitors because they have a tendency to “vent with flames” if mistreated. None of them here are in a position to be mishandled, and should be fine.

- I’m not going to go into the details of the Arduino itself. It is represented by that big block in the lower left corner. The pin numbers are the numbers used in the Arduino documentation.

- I use KiCad to do my schematics and layouts. I’ve posted two complete KiCad projects in a repository on GitHub that you can use to view or modify the schematics and layouts.

- The repository includes datasheets for all of the critical parts. Those are the obvious things (like the ICs) but also the less obvious (like the one inductor used in the circuit.)

- I’ll repeat it again - I’m not an engineer. Pretty much each section of the circuit is built using the suggested circuit from the IC’s datasheet.

The original version of the microwave camera used a satellite finder and an ADC input on the Arduino to detect the RF level. That worked, but there were problems:

- The RF levels were not related to any kind of scale. The meter and the adjustment knob were marked in dB, but there’s no indication of the real level or even if the dB are dBm or some other unit.

- The adjustment knob on the satellite finder seems to subtract an adjustable level from the detected level. Anything below the level set by the knob is just gone. It’s a kind of threshold setting.

- The satellite finder has a small dynamic range - you can’t detect very “dark” objects and very “bright” objects with the same setting on the satellite finder. Worse, you can’t tell before hand how to set the adjustment. You just have to try it and see. Mostly, I ended up with an “overexposed” image followed by an “underexposed” image, followed by one that was more or less OK. That is bad because it takes 20 minutes to make each image.

To fix those problems, I designed the Karl Arduino shield to go with the Karl Arduino software I had already written.

The Karl Arduino shield has the following sections:

- LNB voltage regulator and controller.

- RF level detector with 70dB dynamic range.

- 24 bit analog to digital converter.

- Supporting voltage regulators and voltage references.

I’ll describe each of the parts below.

LNB voltage regulator and controller U1

LNBs are a bit more than simple amplifiers. The LNBs used for satellite TV in Europe have two local oscillator frequencies (and therefore two RF bands they can receive.) They also have two polarizations (horizontal and vertical) that they can use.

The frequency bands are controlled by a 22kHz signal modulated onto the powersupply voltage. 22kHz means “use the upper band (11.70–12.75GHz.)” If the 22kHz tone is not present then the LNBs use the lower band (10.70–11.70GHz.)

The polarization is controlled over the powersupply voltage. 13V to the LNB says “use vertical polarization.” 18V to the LNB says “use horizontal polarization.”

Rather than implement all of that myself, I used an LNBP12SP voltage regulator and controller chip. They are obsolete, though still available. At the time I designed the circuit, I could buy them from Conrad Electronics. The advantage of the LNBP12SP is that it is simple to use. Two digital IO pins control the supply voltage, and a third digital IO turns the 22kHz generator in the chip on or off.

More modern (that is, not obsolete) ICs that do this task require a serial connection to control them (SPI or I2C.) I had to have the SPI port on the Arduino for the analog to digital converter, and I had zero interest in trying to either bit bang SPI or make one port talk to two devices.

Using the LNBP12SP gives me access to both frequency bands and both polarizations with very little code. The original setup with the satellite finder didn’t have this ability.

RF level detector U2

To get around the limited dynamic range of the satellite finder, I selected a MAX2015 RF level detector for use in the new setup. The MAX2015 has a dynamic range of 75dB, and it is fairly easy to compute the RF level in dBm from the output voltage of the chip. The datasheet has all the details. Simply put, the output voltage is linear to the dBm measurement of the RF level. So many millivolts is so many dBm.

There are really just two things to say about this part:

- The MAX2015 is for 50 ohm systems, while satellite TV uses 75 ohms. I checked with the folks over on the Electrical Engineering StackExchange, and ended up just ignoring the mismatch. The consensus was that the loss caused by the impedance mismatch would be less of a problem than trying to blindly (I don’t own a VNA) match the impedances - anything I could build would probably have a worse match than the 50 to 75 ohms.

- I tried to think of everything and do it all right by the datasheet and by general principles. I flubbed it on C4 and C5 at the input to U2. The datasheet says to use 0603 size 680pF capacitors. I used 0805 sized parts. I also should have looked for parts with a resonant frequency above 2.5GHz - forgot that too, and used general purpose parts. It works, but I probably ought to replace them with proper parts someday.

The wide dynamic range frees me from concerns about over or underexposing images. I think it is noisier than a detector with a smaller dynamic range, but I can’t really tell. The ratings in the MAX2015 datasheet aren’t directly comparable to the noise ratings on other level detector ICs, so I just don’t know.

One thing I do know is that the “noisy” output of the MAX2015 limits the precision of the measurements I can make with the 24 bit ADC. The noise is at around 75µV, and the 24 bit ADC can measure down to single digit µV. Still, it’s enough for me to be able to measure things with a resolution of 0.01dBm.

I did include a low pass filter for the output of the MAX2015. That’s R1 and C14, with a cutoff of around 40Hz.

24 bit ADC U4

The ADC on the Arduino has a resolution of 10 bits. My first experiments with the Arduino and the satellite finder used oversampling and decimation to get 13 or 14 bits of resolution. That showed me enough that I could see there were more details to be seen, but that I’d need a lot more resolution. I estimated that I’d need 19 bits to get below 0.01dBm resolution, so a 24 bit ADC was needed.

I settled on the LTC2440 - mostly because I found a project someone else did that showed Arduino code for reading from it. That project also made it seem like it should be pretty straight forward to get good performance on a regular PCB - the example I was following was built on perfboard, deadbug style, and still got the noise down to sub microvolt range.

The LTC2440 worked, but my inexperience tripped me up again. The LTC2440 doesn’t have a buffer for its inputs like some (many?) other ADCs do. The lack of a buffer caused the input to skitter around while the ADC was making measurements. The results were… interesting. Many readings were good, many were bad. It depended on whether or not the output of the MAX2015 could drive the input of the ADC to the proper value before the end of the measurement period. Many times, it couldn’t.

The LTC2440 datasheet actually recommends a 1µF capacitor between the input and ground. Driving that capacitor is just beyond the MAX2015, so I redid the schematic and had another PCB made, including an LTC2050 as a buffer. The LTC2050 (like most opamps) doesn’t like driving capacitive loads at all, so I included R2, R3, and C16 from a Linear Technologies application note on driving capacitive loads. I had my doubts after the simulation in LTSpice showed a most definitely not flat frequency response. When built, the circuit was as unusable as the simulation had predicted, so I simplified it to make a simple non-inverting buffer out of the LTC2050 and put a 43 ohm resistor between the LTC2050 and the 1µF capacitor. That’s well behaved, and the cutoff of 3.7kHz doesn’t bother anything - and the input doesn’t skitter around anymore so I get nice, clean readings.

I selected the LTC2050 because I needed the output to be stable (low drift) - except for the noise, the output from the MAX2015 is mostly a DC signal. I wanted a low noise part because at that point I still had hopes of getting really high resolution readings from the ADC. I hadn’t yet figured out that the MAX2015 was the source of the noise - I thought I still had problems with the powersupply and reference voltage.

Supporting parts

U5 - 3.3V regulator

The MAX2015 operates on 3.3V, but the 3.3V from the Arduino is horribly noisy. Despite filtering, the noise from the Arduino 3.3V made it through the MAX2015 and messed up the readings on the first version. For all the following revisions, I put in an L4931 3.3V regulator to power the MAX2015. The power supply ripple rejection of the MAX2015 could easily handle the output noise of only 50µV from the L4931.

U3 - 5V reference

The LTC2440 needs a low noise voltage reference to work. I picked the LT1019 - and promptly shot myself in the foot again. The LT1019 is low noise, but can oscillate if not handled properly. Proper handling includes selecting the output capacitor. Normally, you don’t need an output capacitor, but the LTC2440 draws currents in spurts, making a capacitor necessary to smooth things out. I originally had like a 100nF capacitor in there. The datasheet points out that the LT1019-2.5V will oscillate with a capacitive load from 400pF to 2.2µF. It turns that it applies to the 5V version as well. The helpful folks on the EE StackExchange pointed out the thing about the 2.5V version and suggested it might apply to the other versions. Either no capacitor or a big capacitor. I plopped in a 4.7µF tantalum - problem solved.

Bits and pieces

In case you are trying to duplicate my boards, I included the datasheets of the power connector (needed for the 24V for the LNB regulator) and the F-connector for the antenna cable to help you find the correct parts. They aren’t in anyway special, except in so far as they have to physically fit the footprints I made. The datasheets are in the repository with the other datasheets.

The final Karl Arduino shield

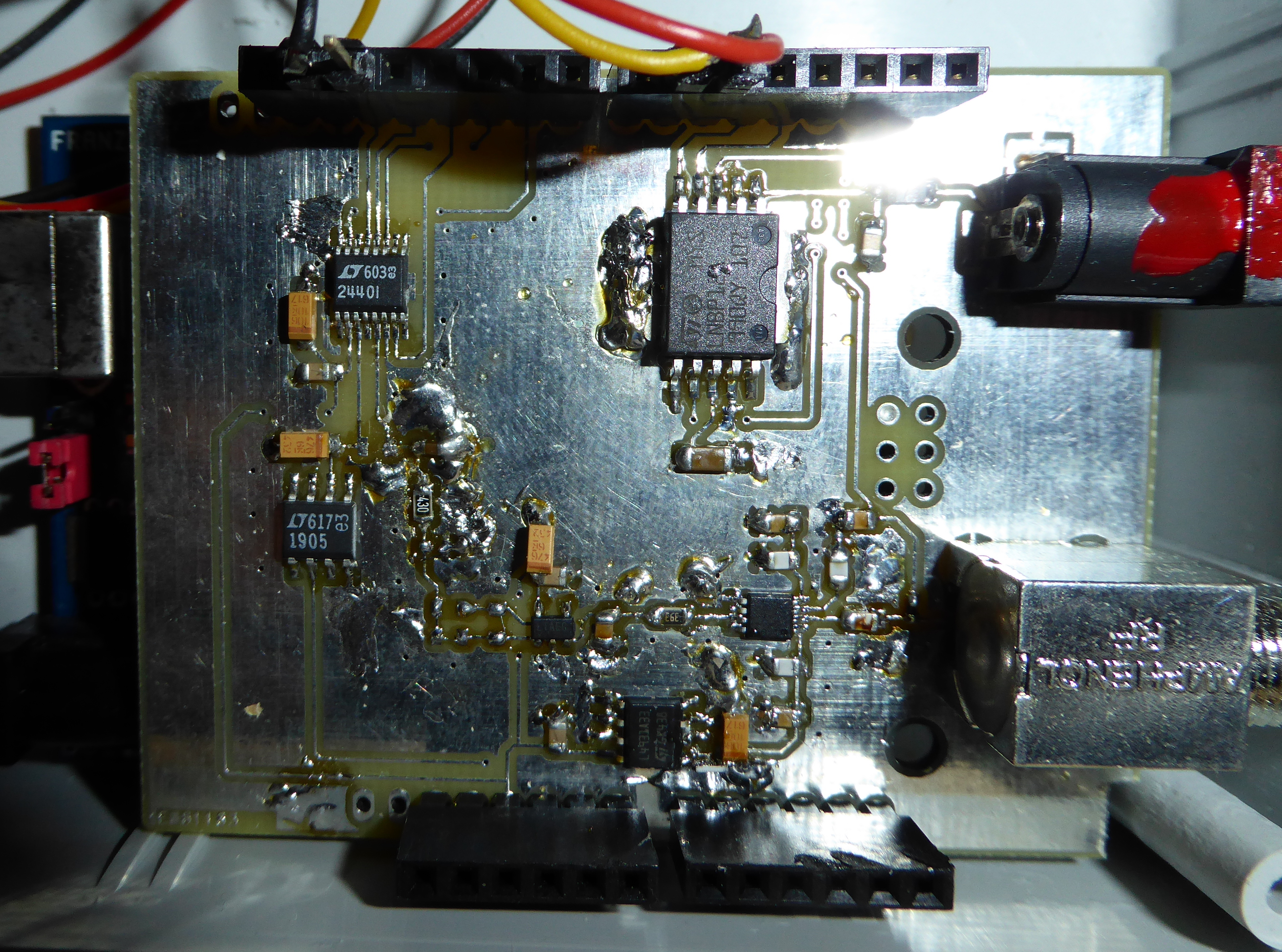

Here’s the currently functional Karl Arduino shield:

| Karl Arduino shield |

|---|

|

| (Open the picture in a separate window and zoom in to see the details.) |

I fiddled with it a lot, adding and removing things to try and improve the noise situation so it looks a little ratty.

I have my PCBs made by EuroCircuits (they are in Germany, so I don’t have to worry about customs charges or having to go pick something up from the Customs office.) This one was made using the (apparently no longer available) “Naked Prototype” option - it cost about 10 Euros less that way than having it made nice and pretty with solder mask and silkscreening.

That’s about it for the electronics.

Next time around, I’ll explain how Karl drives the hardware and talks to the PC.